Living in New Orleans, I have started to find a greater connection to my ancestors, and this past Day of the Dead took me on an unexpected journey through a family food tradition I never thought to question.

A dear friend and high priestess, Kook Teflon, invited us to get to know our great grandmothers and created a beautiful altar and holding space for them and us at the New Orleans Healing Center as a part of their Day of the Dead gathering. The following day, she held a 12 hour fire, where we gathered to share food, song, and stories of our grandmothers. I decided to make my family's favorite pumpkin pie, which I was always told came from my maternal grandmother. As we were sitting around the fire, I realized I had no memory of my grandmother ever making a pumpkin pie. So the next day, I called my mom, and after making this pie countless times and watching her make it even more, for the first time I asked if it really came from my grandmother. "No," she said. "It is from your great grandmother." I couldn't believe it, especially since some of the ingredients seemed unlikely to be from that generation. She said she had the original recipe somewhere and she'd look for it. I was excited and couldn't wait to see this recipe.

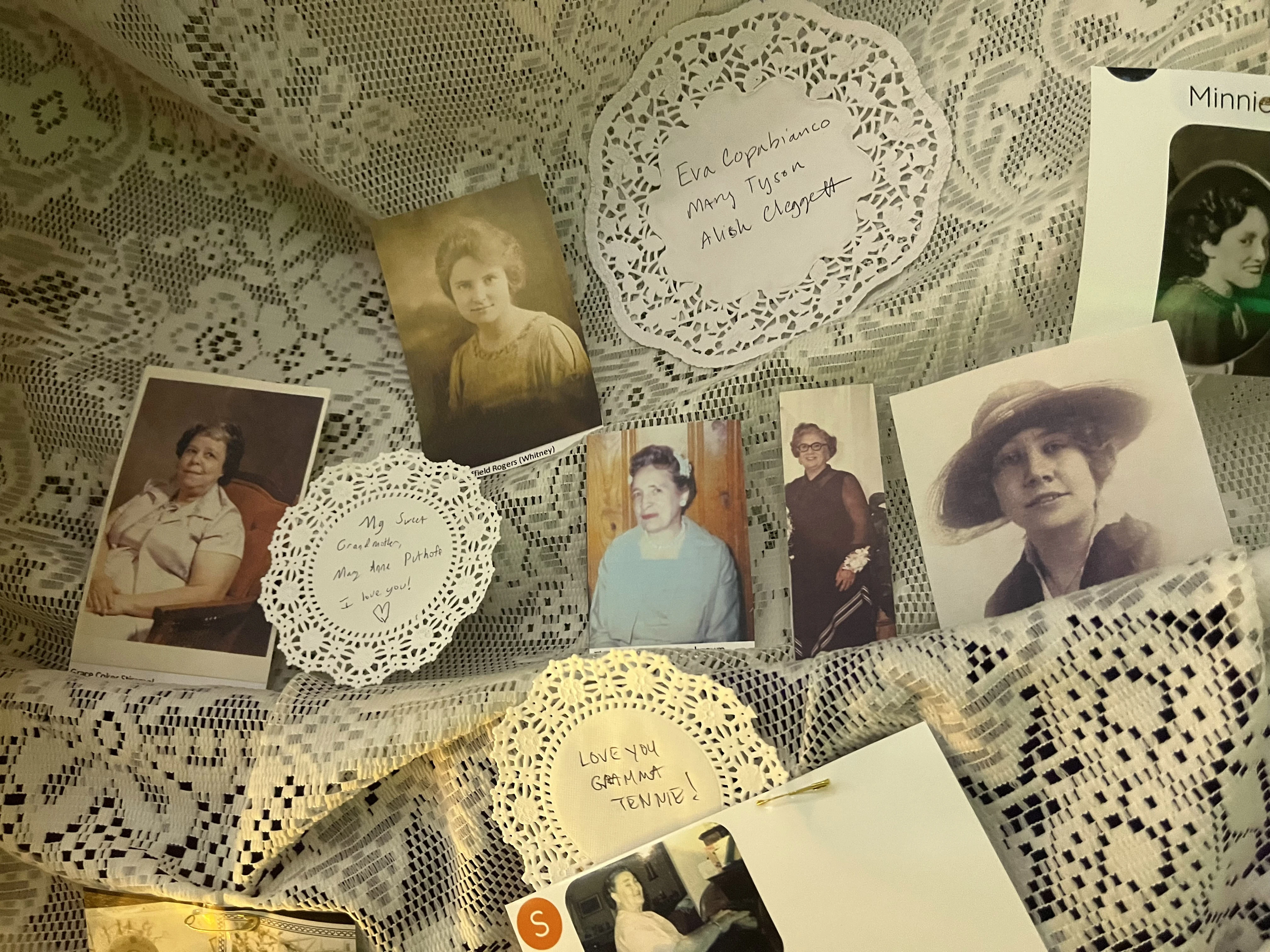

My great greandmothers weaved in Kook's grandmother's web

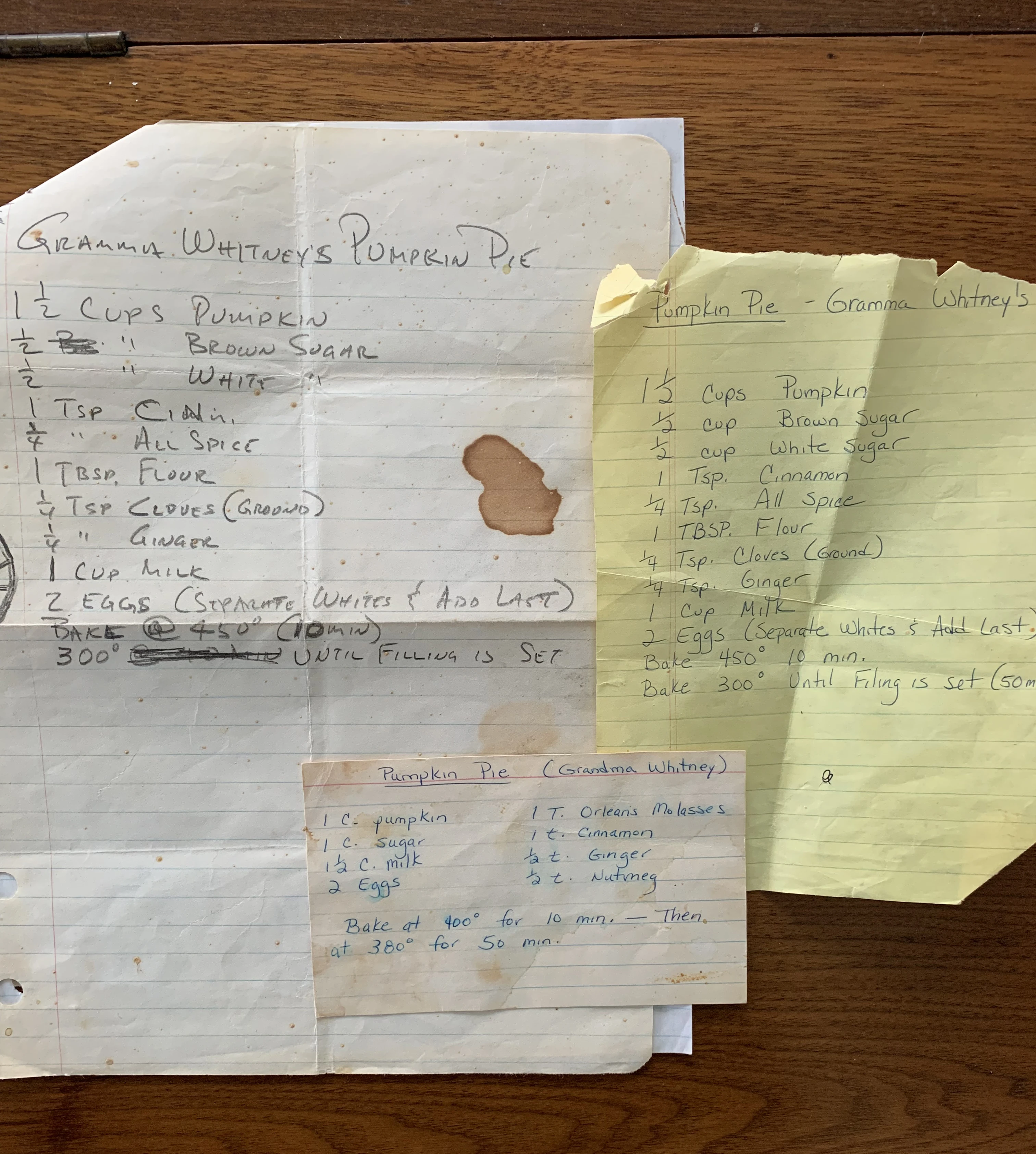

The next day, my mom called. She found the recipe, but said there were actually TWO recipes and neither looked very similar to the recipe we knew and loved. Growing up, my mom always said the secret ingredient to the pie was molasses, and only one of these two had molasses in it. "That's funny," she said. "I wonder why she changed it." It seemed clear that the orignal recipe didn't have molasses in it, so how did it end up at the version we've been making my whole life as "grandma's pumpkin pie?" I set off on a journey of discovery. And making 5 pies in one week.

My great grandmother, Nellie, lived on a farm in western Pennsylvannia. She was supposedly a spitfire, had a doctorate in education, and was the superintendent of the school district. Ever summer as a child, my mom traveled away from her busy New York City life to the spend time on the farm. I asked her if Nellie was a good cook. "No," she laughed. She didn't have time for cooking. Her husband, Charles Whitney, was killed in a mining accident at the age of 30. She had two small children to take care of, and she focused on getting an education and a good job. It was his mother, Grandma Whitney, who was the cook in the family, so it turned out the original recipe was actually from my great great grandmother.

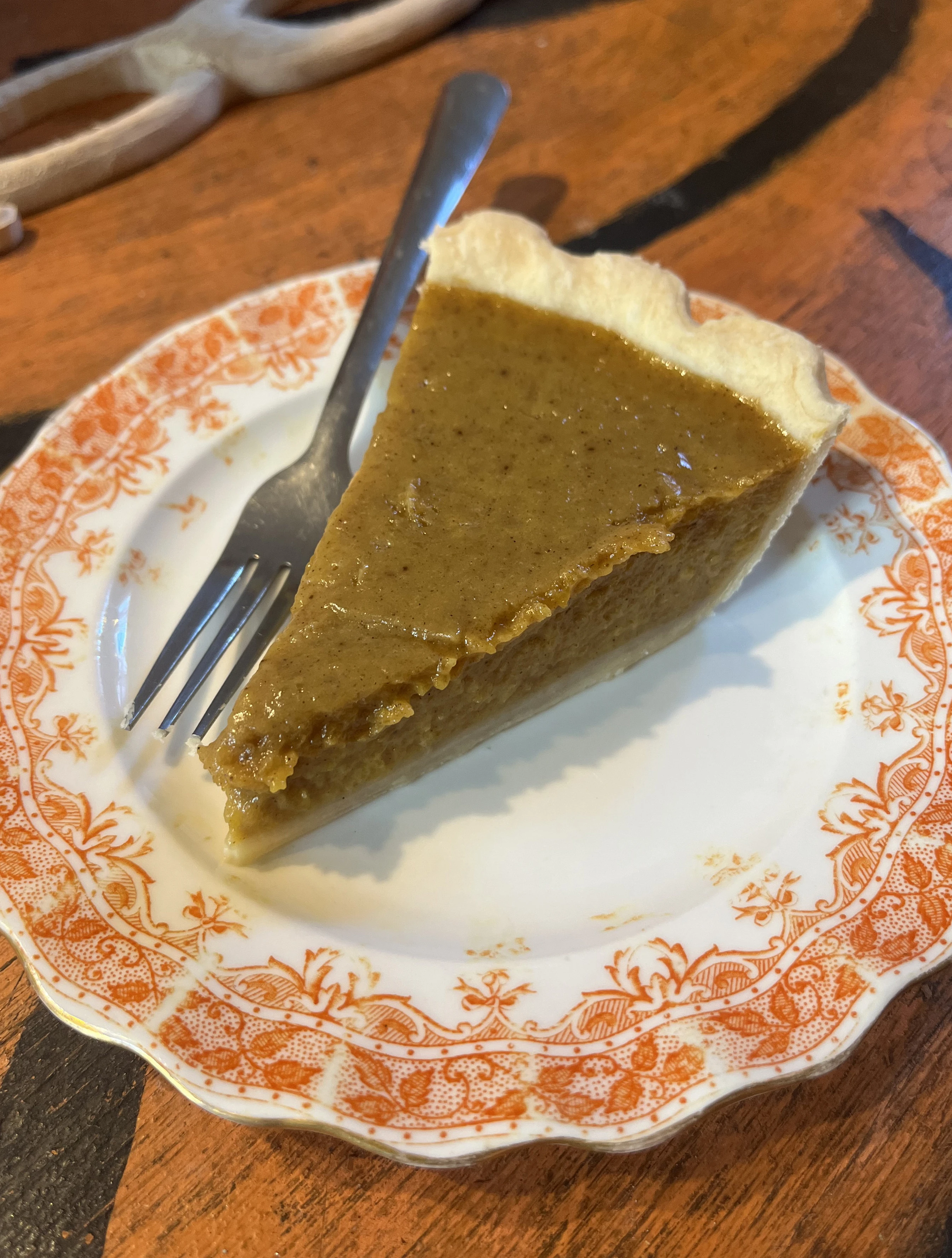

I immediately got to cooking, although I thought a lot about how this pie probably could never be like the original, as she had access to the bounty of the farm--fresh eggs, milk, pumpkin. It took many trips to different grocery stores, wading through the displays of canned pumpkin ready for the upcoming Thanksgiving rush, before I finally found a pie pumpkin to roast. After whipping up all of the ingredianets and filling my pie shell, I could see this was a different pie, with it's light, almost delicate appearance. As I put it in the oven, questioning the much lower cooking tempturature than the pie we were used to, I thought about how she probably did not have an oven with a temperature gage on it. The pie that came out of the oven felt like a treasure. It was so beautiful. After paitinently waiting for it to cool, I took a bite. It was perfect and nothing like the pie of my childhood. It was so delicate and wanted to be savored slowly. The pie I grew up with wanted to be swimming in whipped cream. This pie would have been ruined with the addition of the heavy cream. It was delectable. I thought, why would she change this perfect recipe?

With the main difference being the change to all white sugar and the addition of the molasses, I stared to do some research. I was shocked to find in the late 19th century the manufacturers of refined white sugar launched a smear campaign against brown sugar, and it was so successful the best selling cookbook of the time warned against the use of brown sugar, as it was supposedly inferior and dangerous, containing microscopic, horrifying looking insects and/or germs. None of this was true, but I imagined my grandmother seeing this information and immediately protecting her family by ditching the brown sugar for all white sugar. I also imagined the cookbook advised to add molasses to retain some of the flavor qualities of brown sugar without infesting your family with insects or diseases. I would have ended my research with this assumption, but I noticed the revised recipe called for "Orleans" molasses, and living in New Orleans at the time made me curious.

I had trouble finding a history for an "Orleans Molasses" company, but it threw me down the path of the history of molasses in relation to sugarcane and the slave trade. While this is too complex of a history to fully dive into here, I'll give a very breif overview and encourage you to do more research into this complicated and tragic history. Sugarcane was brought to the Carribean Islands by Christopher Columbus in the late 1400s. In the 1700s, people started growing it in New Orleans, and it steadily grew to become a main export. The early process of refining sugar produced almost as much molasses as granulated sugar, and this excess of molasses needed to go somewhere. It was pushed for cooking as well as to make a cheaper, less alcoholic beer, popular when there was less access to safe, drinkable water. More importantly, it was used to make rum. The North American colonies, primarily New England, found rum to be a valuable trade resource, as it was reportedly the only commodity they could produce without British powers to then sell to them. It also further fueled the slave trade, as rum was traded for slaves to produce more sugar and molasses to produce more rum. To stop the North American colonies from buying/trading for non-British molasses, the British put in place two acts (the Molasses Act of 1733 and the Sugar Act of 1764) to tax non-British molasses imported into the North American colonies, which further strainged relations and led to smuggling molasses. There is a lot more to this history, and I quickly became overwhelmed with how far to dig in relation to making a pie, but now imagined the molasses was added to the second recipe as a way to get more people to use molasses at the same time as getting them to use more refined sugar. I ended up making this pie twice. The first time, I thought I would try the cooking instructions for the first pie, since it turned out so beautifully with the slow bake of the custard. I was wrong. It was a mess, needed a lot longer to bake, and ended up being a weird texture. So I tried again, using the cooking temperatures as written. While it baked better, it was not a pretty pie, and after cooling, my first thought was this was an aggressive pie. It had lost all of the delicacy of the original pie.

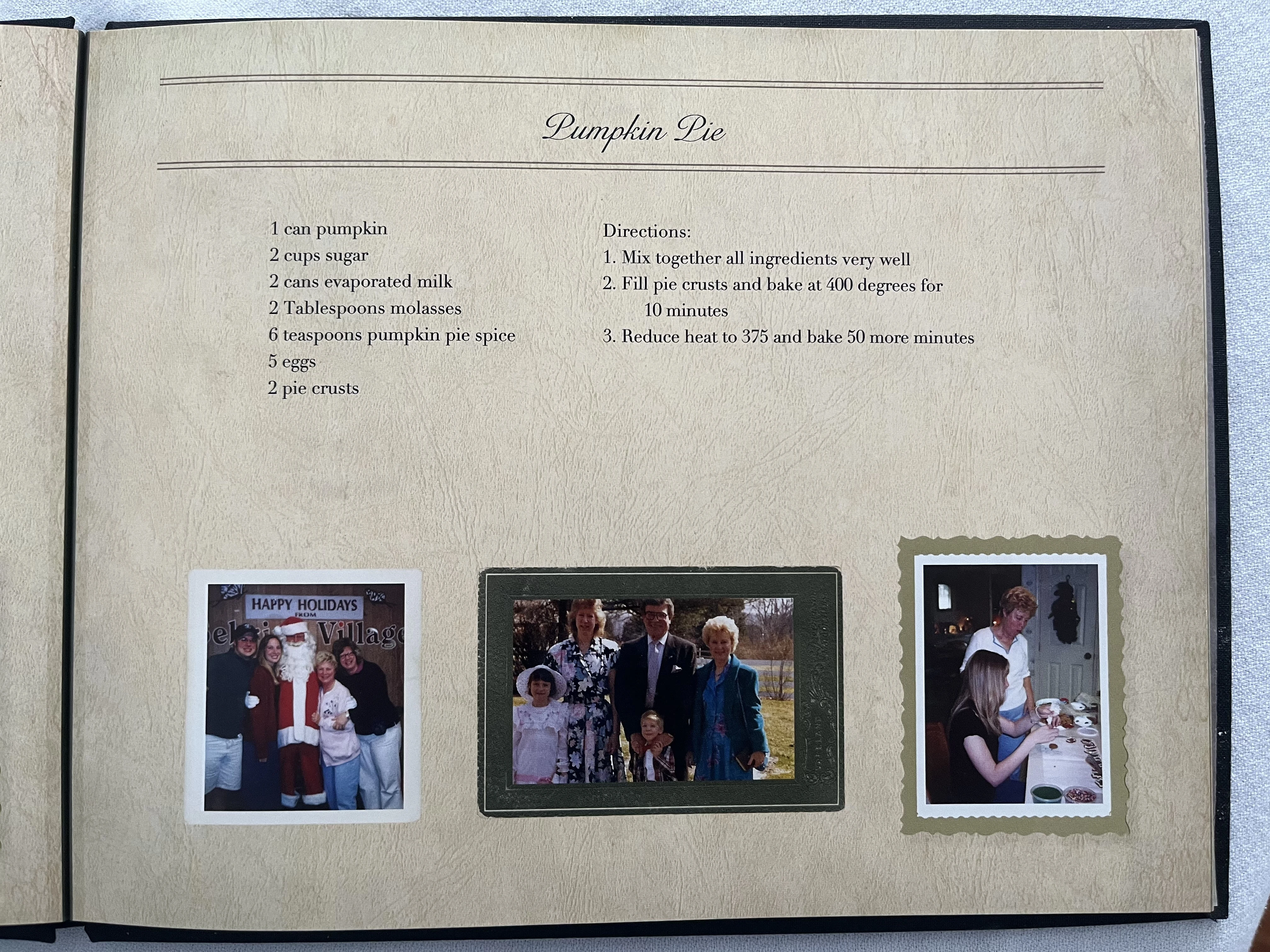

Now onto the pie I grew up with that started this whole journey. I initally thought it must be a 1950s recipe because I assumed evaporative milk was a product of that time. I was wrong. Evaporative milk was invented in the1800s as a mean to preserve and transport milk and was mainly used in wartime for troops. In the 1920s and 30s, it found more widespread use as infant formula. While my great great grandmother, in theory, could have had access to evaporative milk, I doubted she did. I still thought this recipe was a product of the 50s. Doing more research into evaporative milk and pumpkin pie led me to Libby's canned pumpkin. The recipe most people use today for pumpkin pie is influenced by the recipe that started on the back of this can of pumpkin in 1929, which called for canned pumpkin, eggs, milk, sugar, cloves, allspice, and cinnamon, and the recipe that looks most similar to the version I know and love is from the 1950s when Carnation's evaporative milk was added. Although, I found one mention of a 1912 advertisement for Libby's evaporative milk used in a pumpkin pie recipe that seems to have been dropped from the recipe until the 50s. This was prior to the company buying a canned pumpkin business, so the recipe called for cooked pumpkin, eggs, sugar, molasses, cinnamon, ginger, salt, and evaporative milk mixed with water. I read somewhere in all of this research that in taste tests people preferred the evaporative milk version for the taste and texture as well as a decreased cooking time. The canned pumpkin made pie making simpler, the evaporative milk made a more intense dairy flavor, and the reduced water content in both canned products made a denser pie.

In all of this, I can see where the pie recipe morphed throughout the years and landed on the one that was maybe closest to the post brown sugar scare version while also using the canned products to make it quicker and easier, which brought me to thinking about the history of modern food production and movement toward processed foods to simplify our rushed lives. That is a whole other rabbit hole to go down, and while my family favorite pie will always have a special place in my heart, I think I may start making the original version with ingredients as close to the farm freshness that my great great grandmother used on a daily basis, moving back to something delicate to be presented on a pretty plate and savored.

But try out these recipes for yourself! Let me know what you think and take this as an invitation to ask questions about your family favorite recipes. You never know where it may take you.